An Annoying Mathematician Ignites Curiosity Far into the Future

Two thousand years after Archimedes’ time, during the Renaissance and 1600s, mathematicians looked again at his work.

They knew Archimedes’ results were correct, but they couldn’t figure out how the great man had found them.

Archimedes was very frustrating, because he gave clues, but did not

reveal his full methods. In truth, Archimedes enjoyed teasing other

mathematicians, such as Eratosthenes. He would tell them the correct

answer to problems, then see if they could solve the problems for

themselves.

1800 years later, annoyed that they could not figure out what

Archimedes had done long in the past, Renaissance mathematicians pushed

themselves to greater heights, carrying out new research, trying to

measure up to Archimedes.

A Real Life Indiana Jones Style Discovery

The mystery of Archimedes’ mathematics wasn’t solved until 1906, when

Professor Johan Heiberg discovered a book in the city of

Constantinople, Turkey. (The city is now, of course, called Istanbul.)

The book was a Christian prayer book written in the thirteenth

century, when Constantinople was the last outpost of the Roman Empire.

Within Constantinople’s walls were stored many of the great works of

Ancient Greece. The book Heiberg found is now called the Archimedes

Palimpsest.

Heiberg discovered that the book’s prayers had been written on

recycled vellum. The vellum had originally been home to what looked like

mathematics. The monks who wrote the prayers had tried to remove the

original mathematical work, and only faint traces remained of it.

It turned out that the traces of mathematics were actually copies of

Archimedes’ work – a momentous discovery. The Archimedes text had been

copied on to the vellum in the 10th century.

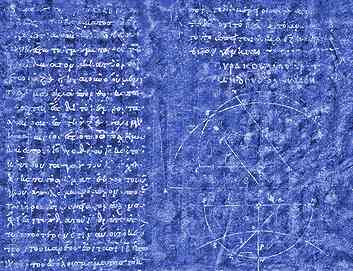

A

false color view of a page from the Archimedes Palimpsest, showing some

of the recovered mathematics. Courtesy of The Walters Museum.

Archimedes Revealed

There were seven treatises from Archimedes in the book including The Method, which had been lost for many, many centuries.

Archimedes had written The Method to reveal how he did mathematics. He’d sent it to Eratosthenes to be lodged in the Library of Alexandria. Archimedes wrote:

“I presume there will be some current as well as future generations who can use The Method to find theorems which we have not discovered.”

And so we learned just how far ahead of his time Archimedes’ math had

been: using summing of series; using his law of the lever to establish

how theoretical mathematical objects would behave; and using

infinitesimals to do work as close to integral calculus as anyone would

get until Newton finally got there 1800 years later.

Archimedes’ Famous Discoveries and Inventions

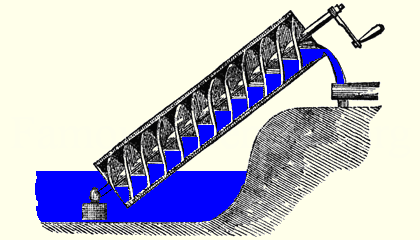

The Archimedes’ Screw

One of Archimedes’ marvelous inventions is the ‘Archimedean Screw.’

This device is rather like a corkscrew within an empty tube. When the

screw turns, water is pulled up the tube, so the screw can pull water up

from a river, lake, or well.

The Archimedes’ Screw

Archimedes is thought to have invented this device when he was in

Egypt, where it’s still used for irrigation. It’s also helpful for

lifting light, loose materials such as ash, grain, sand from a lower

level to a higher level and is still used worldwide for a variety of

purposes.

The Story of the Golden Crown

King Hiero II had given gold to a craftsman to make him a crown. The

crown he got back weighed the same as the gold given to the craftsman,

but King Hiero was suspicious. He thought the craftsman had stolen some

gold, replacing it with silver in the crown. He couldn’t be sure, so he

sent for Archimedes and explained the problem to him.

It was known that gold was denser than silver, so a one centimeter

cube of gold would weigh more than a one centimeter cube of silver.

The problem was that the crown was irregularly shaped, so although its weight was known, its volume wasn’t.

Archimedes is believed to have measured how much the level of water

in a cup was raised by sinking, for example, one kilogram of gold in it,

and comparing this with one kilogram of silver.

If we did this measurement using modern equipment, we would find the 1

kg of gold would raise the water level by 51.8 ml and the 1 kg of

silver by 95.3 ml.

So, if King Hiero’s crown weighed 1 kg, and it raised the water level

by 52 ml or so, then the crown would be pure gold. If the water level

rose more than this, then some of the gold had been replaced by silver.

Archimedes found that the crown was a mixture of gold and silver,

which was bad news for King Hiero, and even worse news for the King’s

craftsman!

Archimedes is supposed to have had the idea of how to solve King

Hiero’s problem when he was taking a bath, noticing the water level

moving as he lowered and raised himself. He was so excited that he

leaped up and ran naked through the streets of Syracuse shouting

‘Eureka,’ meaning, ‘I’ve found it.’ It seems that even thousands of

years ago, scientists had a reputation for being a little crazy!

Calculation of Pi

π is the number you get when you divide the circumference of a circle by its diameter.

To calculate a circle’s area, or circumference, you need to know π.

Archimedes was intensely interested in calculating the mathematical

properties of curved solids, such as cylinders, spheres and cones. To do

this, he wanted to learn more about π.

We now know that π is an irrational number: 3.14159265358979… the

numbers after the decimal point never end, so an exact number can never

be found.

Archimedes knew that the circumference of a circle equals 2 x π x r, where r is the circle’s radius.

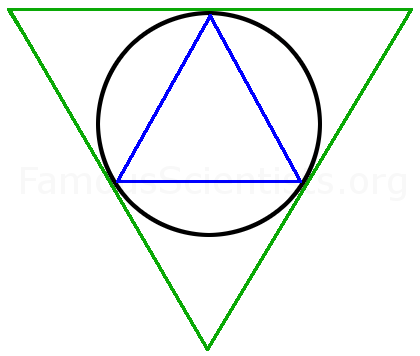

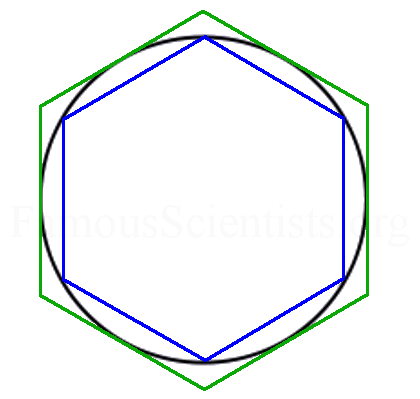

Here is how Archimedes calculated the circumference of a circle of known radius, and hence found π.

He imagined a circle, and in his mind drew an equilateral triangle

inside it, with each point of the triangle touching the circle. Outside

the circle, he drew another equilateral triangle, with each side

touching the circle.

Archimedes drew a mental image of a circle bounded by triangles.

He could easily calculate the perimeter of each triangle, and

therefore he knew the circle’s circumference was greater than the inside

triangle and smaller than the outside triangle.

Then, using a formula he had devised to calculate the perimeter of a

polygon with double the number of sides of the previous polygon, he

repeated his calculation, this time for a circle with a regular hexagon

inside it, and a regular hexagon outside it. The hexagons enclosed the

circle more closely than the triangles had and their perimeters were

nearer to the true circumference of the circle.

Archimedes drew a mental image of a circle bounded by regular hexagons.

In this way Archimedes tightened the limits for the maximum and minimum circumference of the circle.

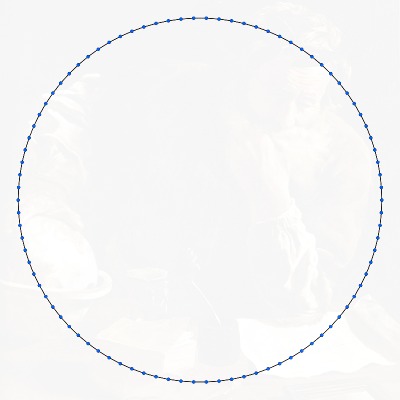

Next, he imagined a circle between two 12-sided regular polygons,

then two 24-sided regular polygons, then two 48-sided regular polygons.

Finally, Archimedes calculated the circumference of a 96-sided regular

polygon inside his circle, and a 96-sided regular polygon outside his

circle.

A 96-sided regular polygon looks the same as a circle unless you zoom in with high magnification.

Is this a polygon, or a circle?

Above is a 90-sided polygon. It has fewer sides than the 96-sided

polygon Archimedes used for his calculation, but you can see that it

looks like a circle to the human eye.

Using the 96-sided polygon, Archimedes found that π was greater than the fraction 25344⁄8069, and less than the fraction 29376⁄9347.

For the world at large, he simplified these numbers, losing a tiny amount of precision to say π was bigger than 31⁄7 and smaller than 310⁄71.

If we average Archimedes’ best upper and lower limits for π, we get

it to be 3.141868115 to nine decimal places. Archimedes’ value of π

differs from the value on your calculator by less than 1 part in 10,000.

In fact, Archimedes’ value of π of 31⁄7 (this is often written as 22⁄7) was used until it became less necessary in our digital age.

Remember that Archimedes did not actually make measurements for his

calculations. They could never have been precise enough. He used pure

mind-power to calculate the areas involved in each situation.

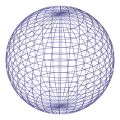

Calculation of the Volume of a Sphere

Archimedes saw his proof of the volume of a sphere as his greatest

personal achievement. His work is remarkable for its similarity to

modern calculus.

Archimedes gave instructions that his proof should be remembered on his gravestone.

We’ve placed this as a separate article here:

The Beast Number

Read about how Archimedes invented the Beast Number, a number so

enormous that the visible universe isn’t big enough to write it out in

full.

And all this because he was fed up of people saying that it was

impossible to calculate how many grains of sand there were on a beach.

We’ve separated this off into a separate article, which you can read here:

Death and Legacy

Archimedes died during the conquest of Syracuse in 212 BC when he was killed by a Roman soldier.

Cicero at Archimedes’ Tomb. Painting by

Benjamin West

Benjamin West

He was buried in a tomb, on which was carved a sphere within a

cylinder. This was his wish, because he believed his greatest

achievement was finding the formula for the volume of a sphere.

Many years later, Cicero, the Roman Governor of Sicily, went looking for the tomb of Archimedes.

He found that it had become overgrown with weeds and bushes, which he ordered to be cleared.

Today, we do not know where Archimedes’ tomb is – it has been lost, probably for ever.

Much of his work has also been lost for ever, but what we know of it leaves us in awe of his achievements from so long ago.

More than 300 years after Archimedes’ death, the Greek historian Plutarch said of him:

“He placed his whole affection and ambition in those purer

speculations where there can be no reference to the vulgar needs of

life.”

Archimedes was a great practical scientist, but above all, he lived

up to the Greek ethos of carrying out blue sky research. He worked on

mathematical problems for the sake of mathematics itself, not to solve

practical problems. Funnily enough, all of his discoveries in

mathematics ultimately did prove to be useful both practically as well

as mathematically.

On his tomb, in addition to the sphere in the cylinder, his name was written in Greek:

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar